Direct-to-consumer startups like Hims and Ro want you to bypass your doctor and buy prescription drugs directly from them. Now, pharma wants in on the action, too.

For customers of Hims, the online retailer of hair loss and erectile dysfunction remedies, the promise of renewed youth and vigor arrives through the mail in a simple beige box. “Future you thanks you,” reads the sans serif type under the top flap. Nestled inside (depending on your order) are ivory-colored cloth bags and bottles filled with pills, gummies, ointments, sprays, shampoos, and—is that a whiff of sandalwood?

“If we can make each point of the [medication] experience amazing and beautiful, hopefully the outcomes will be a lot better,” says Andrew Dudum, the CEO of the two-year-old company, which sells generic versions of prescription drugs like Viagra, Cialis, and Propecia, as well as over-the-counter cures, such as a spray that claims to prevent premature ejaculation. “As a Hims customer, you’ll have a lot of surprises in your box,” he adds, referring to how the company includes playful letters, candles, and even the occasional cologne-scented strip to heighten the multisensory experience of medication delivery. “One thing the [traditional] healthcare system doesn’t do is make you smile.” Even the most sophisticated pharmacists have to concede that, until now, prescription medicine hasn’t offered much of an unboxing experience.

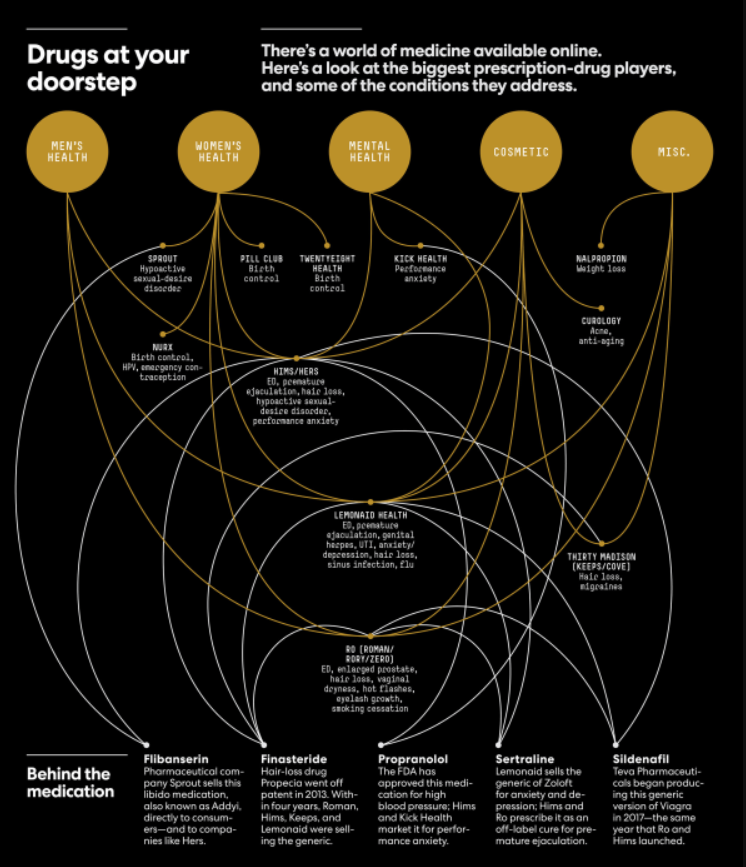

Over the past few years, venture firms such as Maverick Capital, Kleiner Perkins, and Forerunner Ventures have plowed some $500 million into online startups that are seeking a slice of the estimated $61 billion Americans spend out of pocket on prescription drugs every year. And they’re doing it by making drug buying convenient, discreet, and even—why not?—fun. Hims, which raised a $100 million Series C in January at a valuation of $1.2 billion, launched a sister brand last fall, called Hers, which offers prescription acne medication, a female libido enhancer, birth-control pills, and anti-anxiety medication alongside hair-strengthening supplements. Ro, which has reportedly raised $176 million at a $500 million valuation from the likes of FirstMark and Initialized Capital, has three sub-brands: Roman for men’s sexual health, Zero for smoking cessation, and Rory to treat symptoms of menopause, among other things. Birth-control startup Nurx has raised more than $41 million from investors and boasts Chelsea Clinton on its board. San Francisco–based Lemonaid Health, founded in 2013 and the forerunner of the bunch, now sells medication for more than a dozen different conditions, including cold sores and depression.

Want to publish your own articles on DistilINFO Publications?

Send us an email, we will get in touch with you.

In many ways, these online drug peddlers represent the apotheosis of the direct-to-consumer sales model: They take a commodity product (generic medication), simplify the buying process, dress up the packaging, and sell it at a markup, often via a monthly subscription. (Like many a nascent direct-to-consumer startup, these companies are also burning through cash in an effort to acquire new customers.) It’s similar to what companies such as Dollar Shave Club and Glossier do for razors and cosmetics, except instead of circumventing traditional retailers, the telemedicine startups skip the brick-and-mortar pharmacy and replace the in-person doctor’s exam with an online one, sometimes via a video or a phone call, but often merely through an online questionnaire and brief email correspondence. “As consumers, we’re used to accessing almost everything else online,” says Paul Johnson, cofounder and CEO of Lemonaid. “Why shouldn’t we access healthcare online if it’s clinically appropriate and done the right way?”

For now, Hims and its ilk are keeping things simple: They focus on treating a handful of low-risk conditions with medications that have a small incidence of side effects, and they often offer their services cheaply enough that patients can afford them without health insurance. But champions of the model believe that it could become a powerful and flexible tool to prescribe and sell medications for all sorts of chronic conditions—tempting even Big Pharma companies, which already spend tens of billions of dollars persuading people to take their pills, into e-commerce.

The approach is especially suited to today’s Americans, more than half of whom suffer from some sort of chronic condition—and who are increasingly eschewing primary-care doctors. Only 45% of 18-to-29-year-olds even have a primary-care physician, according to a poll from the Kaiser Family Foundation, often due to lack of access or health insurance. In a certain light, offering relatively affordable medications—and medical consultations—online would be a simple fix to some of what ails the healthcare system. But as these startups grow and their model catches on, the balance of power in healthcare could shift profoundly, with big-spending tech startups and pharma companies exercising increasing influence over patients’ drug decisions—and doctors relegated to performing safety checks by the (virtual) cash register.

“Next patient.”

Matthew Roberson, a 44-year-old family-medicine physician who used to work in a Dallas clinic, begins his shift as a gig-economy doctor by sitting down at his desk in his apartment in Pahrump, Nevada, and logging in to the Hims online portal to see which customer the system has matched him with.

He checks the person’s scanned ID first, to ensure that it’s valid and from one of the five states where he’s licensed to practice. (He also checks that the photo resembles an additional picture uploaded by the user.) Next he checks the person’s answers to a detailed medical questionnaire and sees what other medications the person is taking. If he’s prescribing hair loss or acne medication, he’ll review photos of the patient. If he’s writing a prescription for an erectile dysfunction (ED) drug, he’ll check that the person doesn’t have a history of heart conditions or other complicating factors. If anything’s unclear or seems problematic, he’ll message the patient. Otherwise, he reaches out via the online portal to suggest a treatment plan and offer information about the medication. If the patient agrees to the plan, Roberson approves the prescription and moves on. (He estimates that he green-lights about 70% of patient requests.) The initial review takes about three to five minutes. He’ll typically look at between 15 and 20 patient files an hour (including those of people who want to renew their prescriptions), and logs between 150 and 180 hours every month.

Many health advocates, however, worry that direct-to-consumer drug companies are facilitating cursory—or worse, transactional—relationships with doctors, which in some cases begin after the consumer has put the medication in his or her online shopping cart. “The primary interaction is now happening directly between the company that has a huge financial interest in people taking their drugs and consumers who are approaching these websites with not a lot of medical knowledge,” says Matthew McCoy, an assistant professor of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania. “The idea of requiring a prescription is that you talk to a doctor—somebody who’s an expert in these issues—and they help advise you based on particular needs you have. So it’s concerning that companies might be moving the physician to the back of this process.”

Skeptics say that incentivizing people to seek specialized prescriptions online discourages them from scheduling visits with physicians who can evaluate their health in a more holistic way. “With these services, the patient self-diagnoses, chooses the treatment, makes the request, and I worry that the doctor might just rubber-stamp it,” says Steven Woloshin, director of the Center for Medicine and Media at the Dartmouth Institute. “As a doctor, my job is to help the patient make the best decisions. That doesn’t necessarily mean a drug treatment . . . sometimes it’s a non-drug option, or just reassurance.”

In a familiar Silicon Valley refrain, direct-to-consumer telemedicine companies insulate themselves from criticism over treatment decisions by saying that they are merely facilitating interactions between patients and physicians who work for third-party “doctor networks.” “We are a healthcare platform connecting patients to physicians and pharmacists,” says Zachariah Reitano, cofounder and CEO of Ro, “not a drug manufacturer.” To prescribe medications, Hims partners with an outside firm called Bailey Health, which pays physicians between $120 and $150 an hour. Ro works with several networks, which pay doctors per consult, regardless of whether they end up writing a prescription. Notably, though, Ro’s primary doctor network, Roman Pennsylvania Medical, shares office space with the consumer-facing brand, and its owner, Tzvi Doron, serves as clinical director for Ro.

It’s a convenient—and financially advantageous—setup. While drugmakers face strict FDA regulations around how they can market their products, drug platforms have flexibility in how they promote drugs, especially for “off-label” uses that haven’t been approved by the FDA. Sertraline, a generic version of the antidepressant Zoloft, is most often prescribed for anxiety and depression, its FDA-approved use. Roman and Hims, however, offer sertraline as an off-label remedy for premature ejaculation. This past March, Hims counterpart Hers posted an ad on social media promoting the beta-blocker propranolol, an FDA-approved treatment for hypertension, as a cure for performance anxiety. (“Nervous about your big date? Propranolol can help stop your shaky voice, sweating, and racing heart.”) The ad’s casual encouragement for people to use prescription medication to be more suave—a use not yet approved by the FDA—sparked a backlash on social media, but nothing from the FDA. (In response to questions about its regulation of these companies, the FDA referred Fast Company to its policies online.)

“Are these businesses medicalizing everyday experiences or are they actually addressing a gap in the way patients’ needs are served?” asks Patricia Zettler, an assistant professor at the Ohio State University Moritz College of Law who studies FDA law and policy. Nathan Cortez, a professor at Southern Methodist University specializing in FDA law, acknowledges that these companies are seemingly “turning everyday challenges into medical problems that can be treated,” and that advertisements promoting off-label uses of drugs tend to exaggerate the benefits and gloss over the risks. “The federal government has collected billions of dollars over the past few decades going after pharmaceutical companies for off-label promotion,” he says. But the direct-to-consumer startups inhabit a legal gray area: “These companies are not manufacturers, labelers, or medical practitioners. They don’t really fit any description of entities that the FDA regulates.” At least, not yet.

In the meantime, Cortez sees the Federal Trade Commission, which enforces advertising standards, as the regulatory body more likely to rein in these startups’ marketing practices. But it has a lot of catching up to do. In their quest to acquire new customers, direct-to-consumer telemedicine companies have spent hundreds of millions of dollars on advertising on social media, television, and (of course) the New York City subway system. Hims has partnered with the likes of rapper Snoop Dogg to promote its services on TV; its subway ads feature graphically aspirational cacti. Ro has employed playful slogans such as “Erectile dysfunction meds you definitely don’t need, but your ‘friend’ was asking about.” The messages tend to talk about problems and symptoms—the sorts of things you might nervously type into Google. Sexual problems? Hair loss? Anxiety? Depression? There are pills for that—click right this way. In this context, medicine becomes a form of online marketing. And doctors, regardless of their compensation structure or company affiliation, are just one more step in the purchase funnel.

Serial entrepreneur Sid Viswanathan was looking for a new project a few years ago. He had sold his startup Cardmunch, a mobile app that transcribes business cards, to LinkedIn in 2011, and was working at the social network as a product manager. Intrigued by telemedicine, he typed the words pharmacist and startup into LinkedIn and found the profile of Umar Afridi, a pharmacist in East San Jose, California, who described himself as a “startup enthusiast.” They began messaging in 2015 and soon realized that the direct-to-consumer medicine companies that were beginning to raise venture capital would need behind-the-scenes help delivering their products. They launched the online pharmacy Truepill in December 2016.

Today, Truepill acts as pharmacist and fulfillment center for some of the most well-funded internet-based drug sellers, including Hims, Lemonaid, and Nurx. The company is licensed to fill prescriptions for customers in all 50 states, and operates warehouses in San Francisco’s East Bay, Brooklyn, and the United Kingdom, enabling it to ship pills throughout the U.S. and, soon, Europe. (Even men with socialized healthcare want their ED meds quickly and discreetly.) It’s currently developing even more capability. In August, Truepill debuted its own doctor network, making it a one-stop shop for anyone hoping to sell prescription meds directly to consumers.

Viswanathan now has his eye on bigger partners: the pharmaceutical makers themselves. “It’s mind-boggling when you turn on a television and see a drug advertisement, or realize that a drug manufacturer is sending hundreds of sales reps to individual doctors . . . it’s so 20 years ago,” he says. He wants to persuade large-scale manufacturers “not to waste $5 million on a TV ad and instead drive $5 million worth of business through a smarter, more measurable advertising channel and straight into telemedicine.” As he sees it: “The next wave of drug manufacturers will be thinking about how to go direct to consumer—how to actually own that patient relationship.”

That swell is approaching. Pharmaceutical companies spent $6 billion on direct-to-consumer advertisements in 2016, up from $1.3 billion in 1997, according to a recent study by the Journal of the American Medical Association—and they’re starting to sell directly to consumers, too. Nalpropion Pharmaceuticals makes its weight-loss drug Contrave available to patients through the contrave.com website, which uses a Phoenix-based doctor network and pharmacy called Upscript. The site now accounts for 12% of the drug’s sales. When TherapeuticsMD began marketing its Bijuva estrogen therapy this past April, it linked out to a doctor network through the medication’s website. The drugmaker is now considering working with a service like Truepill to further facilitate sales. “We see these models as very positive for the industry,” says TherapeuticsMD president John Milligan. Even Big Pharma is testing the waters: Pfizer sells Viagra through the Pfizer Direct site (although patients must bring their own prescription).

Sprout Pharmaceuticals, maker of the female libido drug, Addyi, takes a more Google-friendly approach to finding its customers. Women concerned about their low sex drive and searching for remedies online might stumble onto the righttodesire.com website, which includes a multiple-choice quiz. If a respondent signals that she’d like to improve her sex life, she ends up on a Sprout Pharmaceuticals page that encourages her to fill out a questionnaire and schedule a $49 phone consultation with a physician who can write a prescription. What the site doesn’t say: Addyi was twice rejected by the FDA before being approved, and some experts question its efficacy. “I hope women will look at the data before they take this drug,” says Steven Woloshin, from the Dartmouth Institute. “The benefits are marginal and there can be important harms.” Sprout CEO Cindy Eckert disputes his assessment, citing the results of three peer-reviewed studies that evaluated the drug’s effectiveness against three outcomes and found improvement. “Addyi scientifically proved effectiveness on those outcomes every single time,” she says. When Fast Company tried purchasing Addyi through Sprout’s website, the prescribing doctor, who works for a network called Firefly XD, didn’t offer any information about the drug’s effectiveness.

Drug companies aren’t the only behemoths that might benefit from bringing the prescription process entirely online. Last June, Amazon spent $753 million on PillPack, which distributes prescription medications by mail. PillPack already enables doctors to upload prescriptions online when a patient requests to begin using the service. It’s not unthinkable that it, too, could add a network of doctors to expedite the process. “And if Amazon does it,” says Milligan, “I could see other players, like Walgreens and CVS, getting into it too.”

And what becomes of the doctors? Joseph Kingsbery, a gastroenterologist based in New York City, spent a few months consulting for K Health, a startup that takes an AI-driven approach to telemedicine (an algorithm analyzes patients’ symptoms, then submits a diagnosis for a human doctor to review). While Kingsbery says he enjoyed advising the company and even helped it recruit doctors, the experience confirmed for him that he never wanted to do telemedicine work himself. Sitting in front of a computer, looking at IDs, checking boxes—”that part does not interest me remotely,” he says. “I love seeing patients. I love interacting with them.”

Date: September 18, 2019

Source: Fast Company