The term “surprise medical bill” describes charges arising when an insured person inadvertently receives care from an out-of-network provider. Surprise medical bills can arise in an emergency when the patient has no ability to select the emergency room, treating physicians, or ambulance providers. Surprise bills can also arise when a patient receives planned care. For example, a patient could go to an in-network facility (e.g., a hospital or ambulatory surgery center), but later find out that a provider treating her (e.g., an anesthesiologist or radiologist) does not participate in her health plan’s network. In either situation, the patient is not in a position to choose the provider or to determine that provider’s insurance network status.

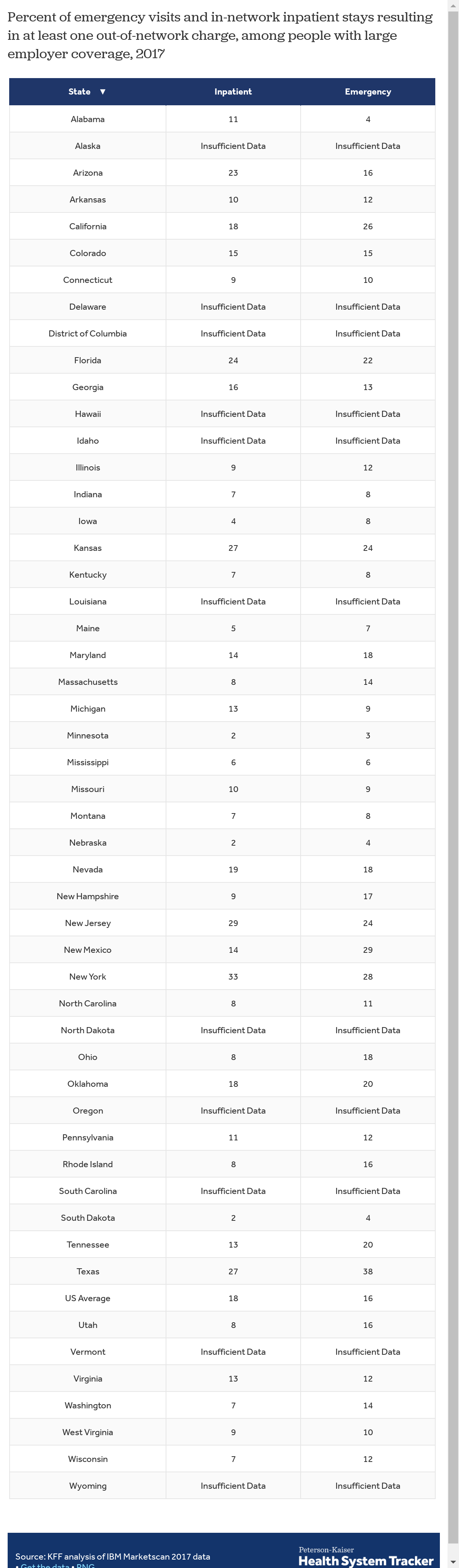

In this analysis, we use claims data from large employer plans to estimate the incidence of out-of-network charges associated with hospital stays and emergency visits that could result in a surprise bill. We find that millions of emergency visits and hospital stays put people with large employer coverage at risk of receiving a surprise bill. For people in large employer plans, 18% of all emergency visits and 16% of in-network hospital stays had at least one out-of-network charge associated with the care in 2017. We also examine state and federal policies aimed at addressing the incidence of surprise billing. Our analysis finds a high degree of variation by state in the incidence of potential surprise billing for people with large employer coverage, who are generally not protected by state surprise billing laws if their plan is self-insured. For people with large employer coverage, emergency visits and in-network inpatient stays are both more likely to result in at least one out-of-network charge in Texas, New York, Florida, New Jersey, and Kansas, and less likely in Minnesota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Maine, and Mississippi.

Background

Surprise medical bills generally have two components. The first component is the higher amount the patient owes under her health plan, reflecting the difference in cost-sharing levels between in-network and out-of-network services. For example, a preferred provider health plan (PPO) might require a patient to pay 20% of allowed charges for in-network services and 40% of allowed charges for out-of-network services. In an HMO or other closed-network plan, the out-of-network service might not be covered at all.

The second component of surprise medical bills is an additional amount the physician or other provider may bill the patient directly, a practice known as “balance billing.” Typically, health plans negotiate discounted charges with network providers and require them to accept the negotiated fee as payment-in-full. Network providers are prohibited from billing plan enrollees the difference (or balance) between the allowed charge and the full charge. Out-of-network providers, however, have no such contractual obligation. As a result, patients can be liable for the balance bill in addition to any applicable out-of-network cost sharing.

Want to publish your own articles on DistilINFO Publications?

Send us an email, we will get in touch with you.

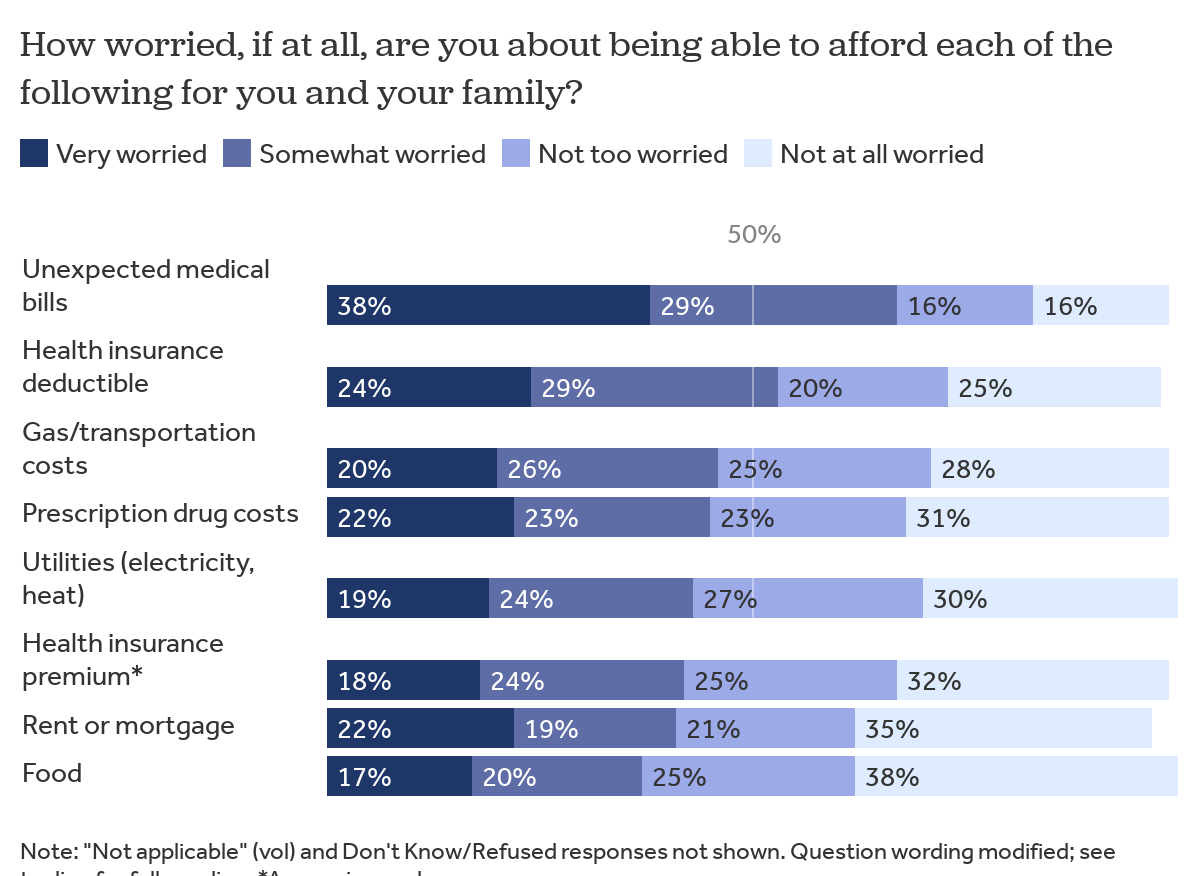

Unexpected medical bills, including surprise medical bills, lead the list of expenses most Americans worry they would not be able to afford. Two-thirds of Americans say they are either “very worried” (38 percent) or “somewhat worried” (29 percent) about being able to afford their own or a family member’s unexpected medical bills.

Large majority are worried about being able to afford surprise medical bills for them and their family

Four in ten (39%) insured nonelderly adults said they received an unexpected medical bill in the past 12 months, including one in ten who say that bill was from an out-of-network provider. Of those who received an unexpected bill, half say the amount they were expected to pay was less than $500 overall while 13 percent say the unexpected costs were $2,000 or more.

More than three-quarters of Americans want the federal government to take action to address the problem of surprise medical bills. Polling shows the public is less interested in the details of how protection against medical bills is accomplished. Opinion is divided over who should pay the cost of the surprise bills – providers, insurers, or both.

Incidence of surprise medical bills

To estimate the incidence of potential surprise medical bills, we analyzed large employer claims data from IBM’s MarketScan Research Database, which contains information provided by large employers about claims and encounters for almost 19 million individuals. By using a claims database, we can examine situations that are likely to result in a surprise out-of-network bill. For example, these data can be used to estimate how often an enrollee accesses services through an emergency room and receives services that are billed as out-of-network. The data can also show when an enrollee had an inpatient admission at an in-network hospital or other facility and yet receives covered services that are billed as out-of-network. The database does not provide complete information about surprise bills, however. In particular, the database contains only paid claims, not denied claims, and so, with respect to in-network inpatient stays, it may not reflect claims for services provided by out-of-network providers if the group plan (say, an HMO), denied those out-of-network claims. In addition, the MarketScan database reflects only the amount of allowed charges under a plan. As a result, the database cannot provide estimates of the dollar amounts of surprise bills – the difference between billed charges and allowed charges – involved in surprise medical bills. For more information, see the Methods.

Emergency services

In an emergency setting, patients are often unable to ensure they go to an in-network emergency room. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) provides partial protection for patients receiving out-of-network emergency care. The ACA requires all non-grandfathered health plans to cover out-of-network emergency services and to apply the in-network level of cost sharing to such services. Health plans are also required to pay a reasonable amount for the out-of-network emergency services.[i] However, the ACA does not prohibit balance billing by facilities or providers for emergency care. As a result, patients can and do receive surprise bills for emergency care from the emergency room facility and from providers who treat the patient in the ER. Surprise medical bills might also arise from the hospital and/or other treating providers if the emergency patient is subsequently admitted for inpatient care.[ii]

Of the emergency room visits in 2017 by people with large employer coverage, we estimate 18% had at least one out-of-network charge (from either the facility, the provider, or both) associated with the visit. This includes out-of-network charges from the emergency facility, emergency room providers, and provider and facility charges associated with a resulting inpatient stay, when applicable.

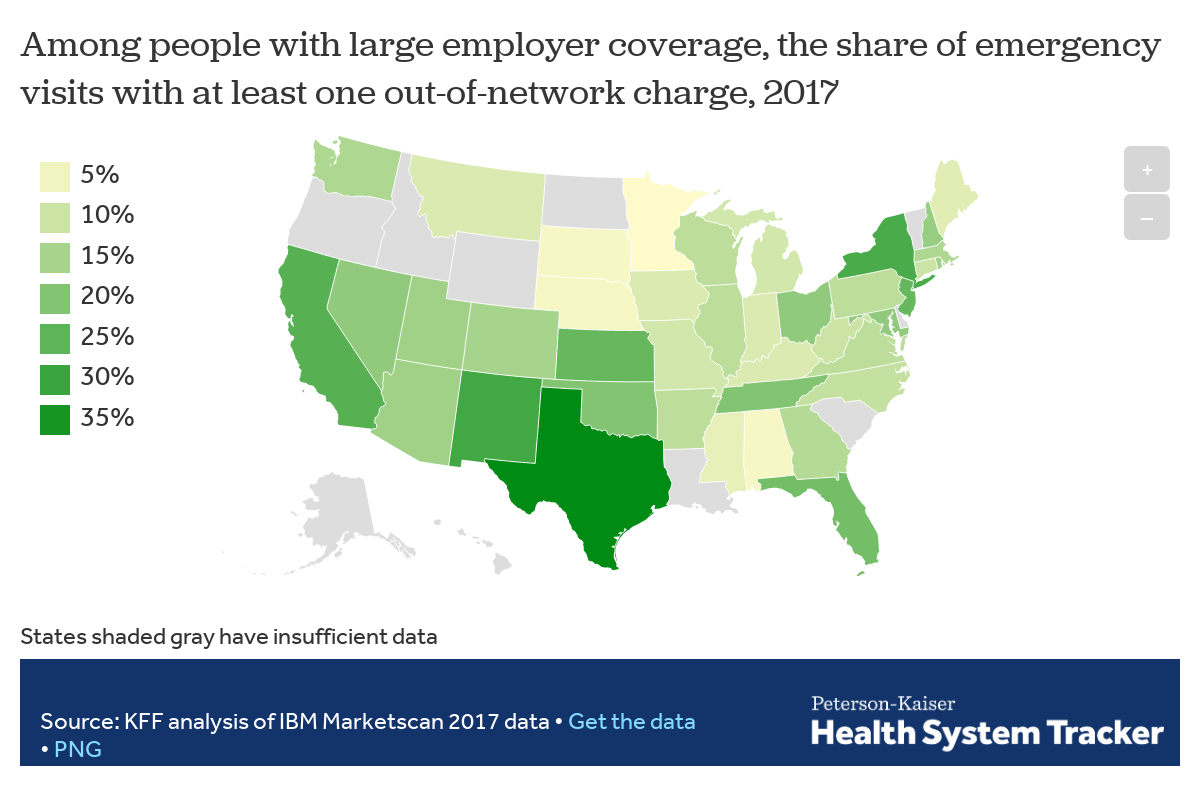

The rate of out-of-network billing in emergency settings for people with large employer coverage varies quite a bit from state to state. About a quarter or more of emergency visits in Texas (38%), New Mexico (29%), New York (28%), California (26%), Kansas (24%), and New Jersey (24%) resulted in at least one out-of-network charge in 2017, while the rate was under 5% in Minnesota (3%), South Dakota (4%), Nebraska (4%), and Alabama (4%). Emergency visits in urban areas (18%) are somewhat more likely to result in at least one out-of-network charge than are visits in rural areas (14%). The data used in this analysis are for large employers who typically self-insure and are therefore not subject to current state protections.

On average, 18% of emergency visits result in at least one out-of-network charge, but the rate varies by state

Most of the potential surprise out-of-network emergency charges observed in this study were from doctors and other out-of-network professionals, rather than from the hospital or emergency facility. Most people with large employer coverage use in-network emergency facilities. Nationally in 2017, 78% of emergency visits by people with large employer coverage were at an in-network facility.

Emergency visits that lead to an inpatient admission are more likely to result in an out-of-network charge (26%) than outpatient-only emergency visits (17%). This is in part due to out-of-network charges that occur after admission, but also due to a higher likelihood of out-of-network emergency professional charges in these cases.

Inpatient care

Surprise medical bills also arise from inpatient admissions, generally when patients are admitted to an in-network hospital or other facility for care. Even within an in-network facility, out-of-network charges for professional services can occur. That is because the doctors who work in hospitals often do not work for the hospitals; rather they bill patients separately and may not participate in the same health plan networks that cover the in-network facility.

The ACA protections for emergency services, described above, do not apply to non-emergency services, including non-emergency surprise medical bills, so in non-emergency admissions, the patient not only is at risk of being balanced billed by the provider, but also faces higher cost sharing under her insurance plan for the out-of-network claims. If the patient’s health plan is a Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) or an Exclusive Provider Organization (EPO) that does not provide any coverage for non-emergency care received out of network, the surprise medical bill claim may not be covered by the health plan at all.

In 2017, among people with large employer coverage who had inpatient stays, the vast majority (90%) were at in-network facilities. Even when patients were admitted to in-network facilities, though, 16% of these stays resulted in at least one out-of-network charge for a professional service. As described above, in many of these cases, the patient not only is at risk of being balanced billed by the provider, but also likely faces higher out-of-pocket costs under her insurance plan for the out-of-network claims.

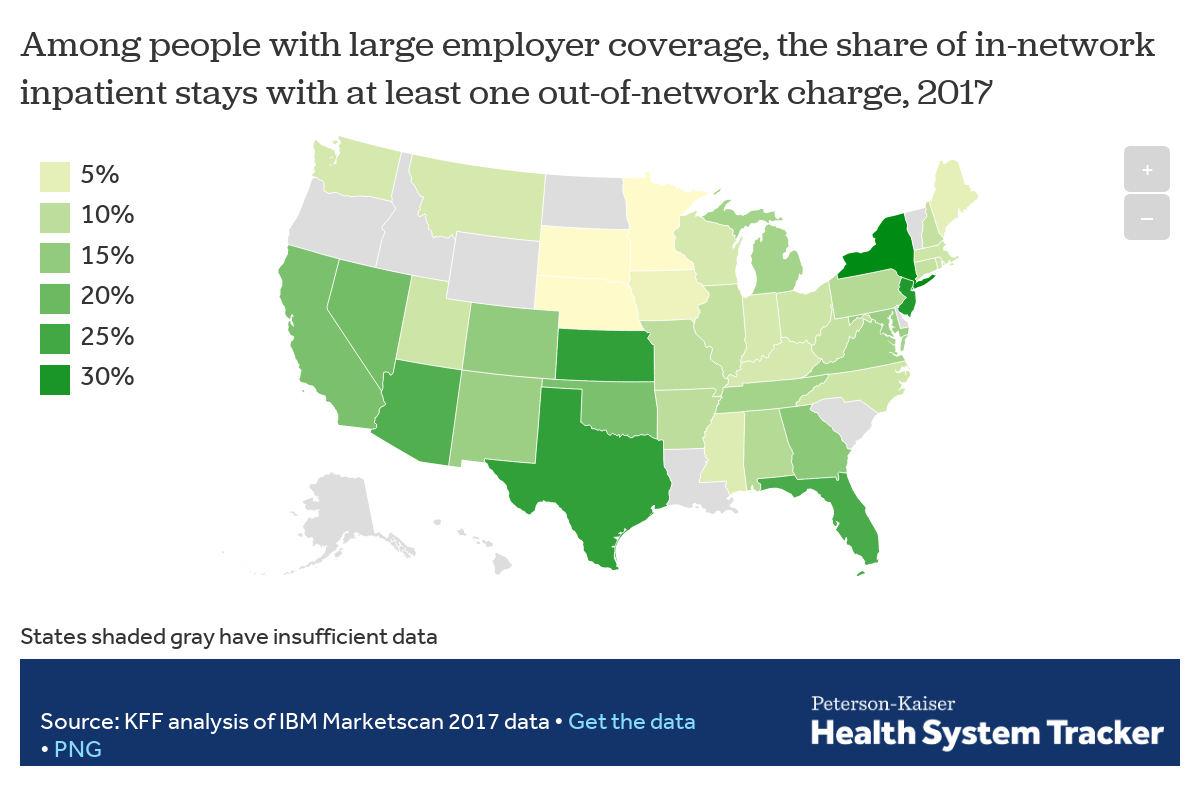

The rate of out-of-network charges for services at in-network inpatient facilities ranged from 2% of in-network inpatient stays in South Dakota, Nebraska, and Minnesota, to about a quarter or more in New York (33%), New Jersey (29%), Texas (27%), and Florida (24%). Inpatient stays in urban areas (16%) are somewhat more likely to result in at least one out-of-network charge than are stays in rural areas (11%).

On average, 16% of in-network inpatient admissions result in at least one out-of-network charge, but the rate varies by state

State action on surprise medical bills

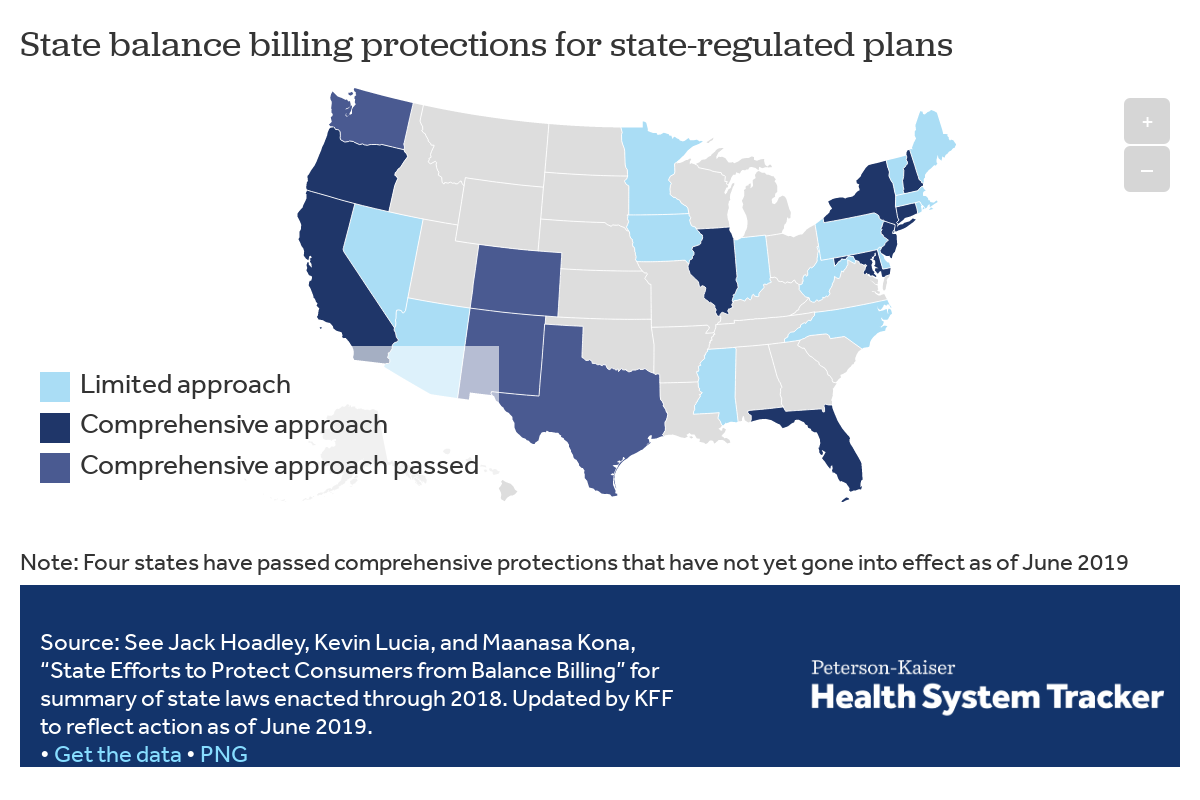

States have begun to enact laws to protect some patients from surprise medical bills, though, as discussed below, these state laws generally do not apply to people with large employer coverage whose employers self-insure. At least nine states have enacted and implemented laws taking a comprehensive approach to surprise bills (California, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Maryland, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, and Oregon). Four more states – New Mexico, Washington, Colorado, and Texas enacted new surprise medical bill laws in 2019 that have not yet taken effect.[iii]

States vary in their approach to surprise bills

The comprehensive state laws share common features:

Hold patients harmless

Comprehensive state laws hold consumers harmless against surprise medical bills. The hold-harmless protection generally involves two types of requirements – one for state-regulated health insurers, and one for providers. Insurers are required to cover out-of-network claims and apply in-network level of cost sharing for surprise medical bills. In addition, laws prohibit providers from balance billing patients covered by state-regulated plans; instead, the out-of-network provider is limited to collect no more than the applicable in-network cost-sharing amount from patients in cases of surprise medical bills.

State laws may also require notice to consumers about their rights and protections. New York, for example, requires state-regulated insurers to include prominent, standardized notice on the explanation-of-benefits (EOB) statement summarizing consumer rights regarding surprise medical bills. Notices also give consumers information about where they can file complaints or receive help. In California and New Mexico, out-of-network providers also are required to include prominent notice in billing invoices and other written communications pertaining to surprise medical bills that the consumer is not liable to pay more than the in-network cost sharing amount.

Resolve payment for surprise bills

After indemnifying the patients, comprehensive state laws then provide for resolution of the payment amount for surprise medical bills. Approaches vary, with some states adopting a payment standard for all applicable surprise medical bills, while other states establish a dispute resolution process that insurers and providers can use to arrive at a payment amount for each surprise medical bill. States sometimes use a combination of both approaches.

California’s surprise medical bill law, for example, requires state-licensed managed care plans to pay out-of-network providers the greater of 125% of the amount Medicare fee-for-service would pay, or the average contracted amount the managed care plan pays for the same/similar service in that geographic region.

New York’s law uses a binding arbitration process to resolve payment disputes. The formal process is used infrequently, however, because the law incentivizes insurers and providers to reach agreement on their own. Under the New York system, the insurer and provider first negotiate to settle the surprise medical bill. If they can’t agree, an arbitration process can be invoked; each party submits its best offer and the arbiter decides which offer wins. The losing party must pay the cost of arbitration, which typically can be $300 to $500. This so-called “baseball style arbitration” process incentivizes both plans and providers to try to resolve surprise bills informally, if at all possible. State regulators indicate most surprise bills subject to the New York law are resolved informally; New York’s formal dispute resolution process was used for 1,096 claims in 2017.

Limits to state law protections

All states have limited jurisdiction to protect privately insured residents from surprise medical bills due to the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, or ERISA. This federal law preempts state regulation of employer-provided health benefit plans. That means states are preempted from requiring employer plans to cover out-of-network surprise bills; they are also preempted from requiring these plans to apply in-network cost sharing to out-of-network surprise bills; and they are preempted from requiring these plans to settle payment disputes with out-of-network providers over surprise bills using state-established payment rules or procedures. Though ERISA allows states to regulate the group health insurance policies that some employers buy from insurance companies, 61% of covered workers (and 81% of those in large firms) are covered under self-insured group health plans that are beyond the reach of state regulation. Our estimates of surprise medical bills under large group health plans largely reflect consumers whose plans would not be subject to state law.

In addition, a number of states have enacted less comprehensive protections against surprise medical bills for the plans they regulate. Some states, for example, require only that consumers be notified by their health plan (or hospital) that they might encounter surprise medical bills, but do not impose other requirements on health plans or providers that would shield consumers from the cost of surprise medical bills. Some state laws protect consumers against surprise medical bills for emergency care, but do not apply to bills from out-of-network providers rendering care in in-network hospitals. Some state surprise bills laws apply to HMOs but not to other state-licensed insurers.

Federal legislation

Because ERISA preempts states’ abilities to regulate self-insured plans, federal action would be necessary to address certain aspects of surprise bills for people enrolled in these plans. On May 9, 2019, President Trump called on Congress to enact bipartisan legislation to end surprise medical bills. The President called for a prohibition on balance billing for all emergency care and for services from out-of-network providers that patients did not choose themselves. He also said that surprise bill protections should apply to all types of health insurance, including group and non-group.

Bipartisan members of the Senate have since introduced legislation (S. 1531) to stop surprise medical bills. In addition, a bipartisan discussion draft bill has been released by the Chair and Ranking Member of the House Energy and Commerce Committee. And, the Chair and Ranking Member of the Senate Health Education Labor and Pension (HELP) Committee recently introduced a bipartisan bill, S. 1895.

All three measures would apply to out-of-network emergency claims. One of the bills, S. 1895, would also apply to air ambulance claims; otherwise none of the measures specifically mention emergency transport services. All three measures would also apply to non-emergency services provided by out-of-network providers at in-network hospitals and other facilities. In addition, S. 1531 and S. 1895 would apply to non-emergency care provided at a non-network facility if the patient is admitted after receiving emergency care and cannot be moved without medical transport to an in-network facility. One bill, S. 1531, would also apply to surprise bills for services ordered by an in-network provider in the provider’s office but delivered by an out-of-network provider (such as lab tests or imaging).

All three measures would hold patients harmless from surprise medical bills. All would require health plans and insurers to cover the out-of-network surprise bill and apply the in-network level of cost sharing; and all would prohibit out-of-network facilities and providers from balance billing on surprise medical bills. All bills would apply to group health plans, whether fully-insured or self-insured, and to individual health insurance.

To resolve the payment amount for surprise bills, the three bipartisan measures take somewhat different approaches. The House Energy and Commerce Committee discussion draft and S. 1895 would require health plans to apply the median in-network payment amount for that service within the geographic region. S 1531 also requires health plans and issuers to initially pay the median in-network rate for surprise medical bills; but it provides for an independent dispute resolution (IDR) process if the out-of-network provider requests. The IDR process would be similar to that established under the New York’s statute. Both parties would submit their best offer, the IDR entity would make a binding decision about which offer prevails, and the non-prevailing party would pay for the cost of the IDR process.

S. 1985 also includes a provision for a national claims database, including data from self-insured employer plans, Medicare, and participating states. The House discussion draft and S. 1531 also include other provisions to promote transparency. S. 1531 would require all health plans and insurers to periodically report data on all in-network and out-of-network claims, including specific reporting on surprise medical bill claims and data on patient financial liability attributable to cost sharing and balance billing. The House discussion draft appropriates $50 million for states to establish or maintain all-payer claims databases, which could be used to track the incidence of surprise medical bills and to monitor compliance.

In addition to the three bipartisan legislative measures, other, less comprehensive federal bills have been introduced this year. For example, a House bill, HR 861, would prohibit balance billing by providers for certain surprise medical bills, though this bill would not require health plans and insurers to cover surprise medical bills with in-network-level cost sharing, nor would this bill set any standard or process to resolve the payment amount for surprise bills. HR 861 would apply to all group health plans and insurers, as well as to Medicare and Medicaid plans and to other governmental employee plans. A Senate bill, S. 1266, would protect enrollees of self-insured employer plans from certain surprise medical bills, but would not apply to other health plans or insurance.

Discussion

We find that millions of emergency visits and hospital stays left people with large employer coverage at risk of a surprise bill in 2017. Our analysis of large employer health plan claims finds that potential surprise medical bills are a common problem – affecting 18% of emergency care visits and 16% of in-network inpatient stays. The rate of these potential surprise bills varies from state-to-state, with Texas, New York, Florida, New Jersey, and Kansas having among the highest rates of out-of-network charges associated with both emergency care and in-network hospital stays among people with large employer coverage. Minnesota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Maine, and Mississippi, by contrast, had among the lowest rates of out-of-network charges for both emergency and in-network hospital care for people with large employer coverage. The incidence of surprise medical bills in small group or non-group health plans may be different and was beyond the scope of this study.

By definition, surprise bills are beyond the ability of consumers to anticipate or avoid; and surprise bills generate expenses that health insurance does not cover and that can be financially burdensome to patients. States have started taking action – establishing requirements for both the health plans and the providers they regulate in order to shield consumers from surprise medical bills. However, ERISA preemption means state laws cannot reach the vast majority of consumers with private coverage through employer-based plans. The high rates of surprise medical bills that we observe in California and New York, which have adopted comprehensive state statutes, demonstrate the limits of state regulation of surprise bills.

National consensus on surprise medical bill protections seems to be emerging. Members of Congress are working in a bipartisan manner to develop legislation and the President has urged enactment of a federal law to protect patients from surprise medical bills. The insurance industry, employer organizations, and hospital and physician groups have also urged measures to protect patients from surprise medical bills, though the debate continues over how much providers should be paid for surprise medical bills.

In particular, hospital and physician groups have urged reliance on negotiation or mediation to resolve surprise bills, and generally opposed use of a fixed payment standard. They argue a fixed payment standard might not be sufficient, might incentivize insurers to rely on default payments rather than contract with providers to join networks, and might lead to broader federal rate setting for provider payments. On the other hand, health insurers and employer groups have recommended a federal payment standard as a less complex and costly approach to resolving millions of surprise medical bills each year.

It remains to be seen whether disagreement over how to resolve payment amounts for surprise bills can be resolved, or if it could derail legislation to protect consumers from these bills.

Appendix

Methods

We analyzed a sample of medical claims obtained from the 2017 IBM Health Analytics MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database, which contains claims information provided by large employer plans. We only included claims for people under the age of 65. This analysis used claims for almost 19 million people representing about 22% of the 86 million people in the large group market in 2017. Weights were applied to match counts in the Current Population Survey for enrollees at firms of a thousand or more workers by sex, age, state and whether the enrollee was a policy holder or dependent. Weights were trimmed at eight times the interquartile range.

The advantage of using claims information to look at out-of-pocket spending is that we can look beyond plan provisions and focus on actual payment liabilities incurred by enrollees. A limitation of these data is that they reflect cost sharing incurred under the benefit plan and do not include balance-billing payments that beneficiaries may make to health care providers for out-of-network services or out-of-pocket payments for non-covered services.

Inpatient claims were aggregated by admission and outpatient claims were aggregated by the day (‘outpatient days’). Each claim on the inpatient and outpatient services files has a variable (‘ntwkprov’) that indicates whether or not the provider or facility providing the service was in the health plan’s network.

We defined an emergency room visit as an outpatient day or admission that included at least one claim in the emergency room (as defined by “stdplac”). Some admissions may include an emergency room claim, and an out-of-network service that took place outside of the emergency room. In total, there were 15 million ER visits, six percent of which were associated with an inpatient admission.

In-network admissions were defined as admissions that included an in-network room and board charges. Some in-network admissions may include out-of-network facility charges. In total, there were about 3.5 million in-network admissions. Data are not presented for states with fewer than 3,000 unweighted emergency room visits or 500 in-network admissions or where an insufficient number of data contributors submitted information.

Endnotes

[i] Federal regulations require health plans to pay the greater of 3 amounts for out-of-network emergency services (net of the applicable in-network cost sharing): (1) the amount negotiated with in-network providers for the emergency service; (2) the amount the plan typically pays for out-of-network services (such as the usual, customary, and reasonable charge); or (3) the amount that would be paid under Medicare for the emergency service.

[ii] Section 2719A of the Public Health Service Act defines emergency services in the same way as the federal Emergency Medical treatment and Labor Act of 1986 (EMTALA). However, the application of EMTALA to patients admitted as inpatients from the emergency room has been disputed and litigated. Federal courts have taken different views as to a hospital’s “stabilization obligation” under EMTALA when it comes to inpatients. See, for example, https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20101228_RS22738_a6cc21b68c20d1982533d6249774e019179ef6a5.pdf

[iii] See Jack Hoadley, Kevin Lucia, and Maanasa Kona, “State Efforts to Protect Consumers from Balance Billing” for summary of state laws enacted through 2018. In the 2019 legislative session, New Mexico enacted a new law protecting residents from surprise medical bills, both for emergency and non-emergency services, under state-regulated health insurance. The law takes effect January 1, 2020. It requires state-regulated health plans to provide in-network level of coverage for surprise medical bills and prohibits providers form balance billing patients. The law also provides that surprise out-of-network bills will be paid at the 60th percentile of the insurer’s allowed charge for the service performed by an in-network provider, but no less than 150% of the applicable 2017 Medicare payment rate. The state of Washington also enacted a surprise medical bill law in 2019. Similar to the New Mexico law, Washington requires state-regulated plans to cover surprise medical bills for both emergency and nonemergency services at the in-network level of cost sharing and prohibits providers from balance billing patients. The Washington law establishes a mediation process that health plans and providers must use to resolve the amount of each surprise medical bill if the plan and providers cannot successfully negotiate an amount on their own. Colorado’s new law also becomes effective January 1, 2020. It applies to emergency and non-emergency surprise bills, requiring state-regulated health plans to provide in-network level of coverage for such bills and prohibiting provider balance billing. The law establishes payment rate benchmarks for surprise bills, based on the health plan’s payment rate for comparable in-network providers or based on a measure of the in-network payment rates by all plans in the state’s all-payer-claims database. Out-of-network providers can appeal these payment rates to a mediation system in certain circumstances. Finally, a new law enacted in Texas will apply to surprise medical bills beginning January 1, 2020. The Texas law requires state-regulated plans, including state employee and teacher plans, to cover surprise medical bills for both emergency and nonemergency services, including diagnostic lab and imaging services ordered by an in-network physician. Plans must cover out-of-network surprise bills with in-network level of cost sharing and providers are prohibited from balance billing patients. Texas requires plans to make an initial direct payment to the out-of-network provider for the surprise bill. The provider can then request an independent dispute resolution process. For hospitals and other facilities, this is a mandatory mediation process that the facility and insurer must use to resolve the amount of the surprise bill. If agreement cannot be reached, either party can bring a civil action in court. For other providers, Texas will make a mandatory arbitration process available. The arbitrator will make a binding determination of the payment amount for the surprise bill. A mandatory informal settlement conference is required before either mediation or arbitration begins. Under both processes, the fees for mediation or arbitration must be split evenly between the health plan and the facility/provider.

Date: June 26, 2019

Source: Health System Tracker